The nineteenth century saw a rise in institutions for those with disabilities. Some were notoriously inhumane while others helped build communities. As a postcard sent to an asylum superintendent in Kansas reveals, institutions sometimes cut patients off from their families. Some institutionalized people never left the asylum and communication between them and their families was limited or even nonexistent. On the other hand, some institutions helped build communities around specific disabilities like deafness or blindness. Children removed from their families and placed in special schools continued to communicate with the world, often in the form of artistic expression. Schools for the blind taught literacy so that blind people could build a community together. In addition to Braille, attempts to make an alphabet for the blind were popular, showing that a system of communication was both wanted and needed. This page highlights the types of institutions and communities that existed in 19th century America.

For more detailed descriptions of the images, see the hyperlink below each picture.

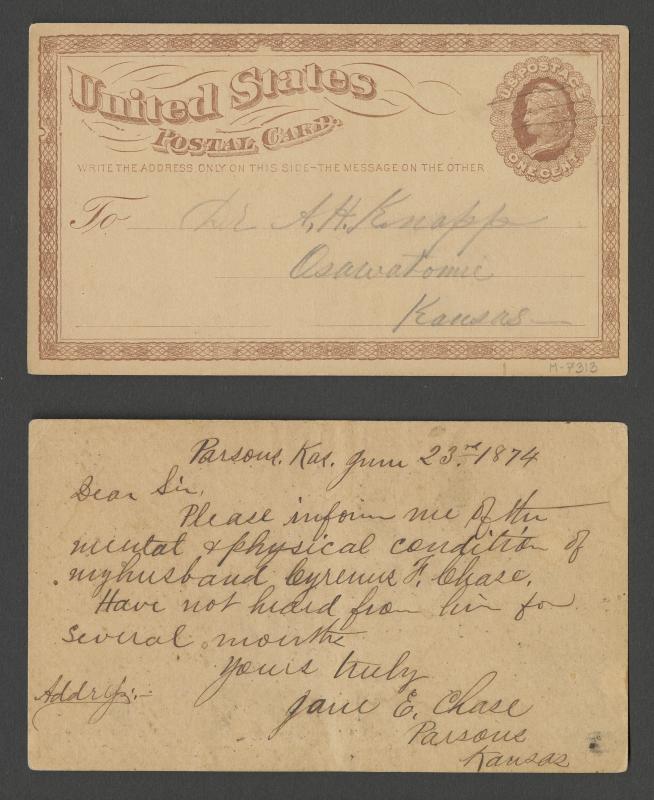

3 x 5 postcard with address on the front and letter on the back, dated June 23, 1874

Although insane asylums began as rehabilitation facilities, they soon became like prisons. As this collection of postcards to the Kansas Insane Asylum explores, asylums were secretive about their health care practices. Many patients were trapped there despite their improved physical and mental health. The late nineteenth century saw the publication of many infamous narratives of mistreatment of patients in insane asylums across the United States. Lydia Smith’s memoir of the Kalamazoo asylum describes attendants physically assaulting the patients: “Some times Miss Peabody would be very kind to this old lady ; then again she would beat her in the most cruel manner” (Smith, 1879). The postcard depicted comes from a wife asking for information about her husband at the Kansas Insane Asylum. The desperation present within her writing is especially palpable; the language shifts between politeness and urgency.

“Dear Sir,

Please inform me of the mental and physical condition of my husband by Cyrenus F. Chase

Have not heard from him for several months. Your truly, Jane E. Chase”

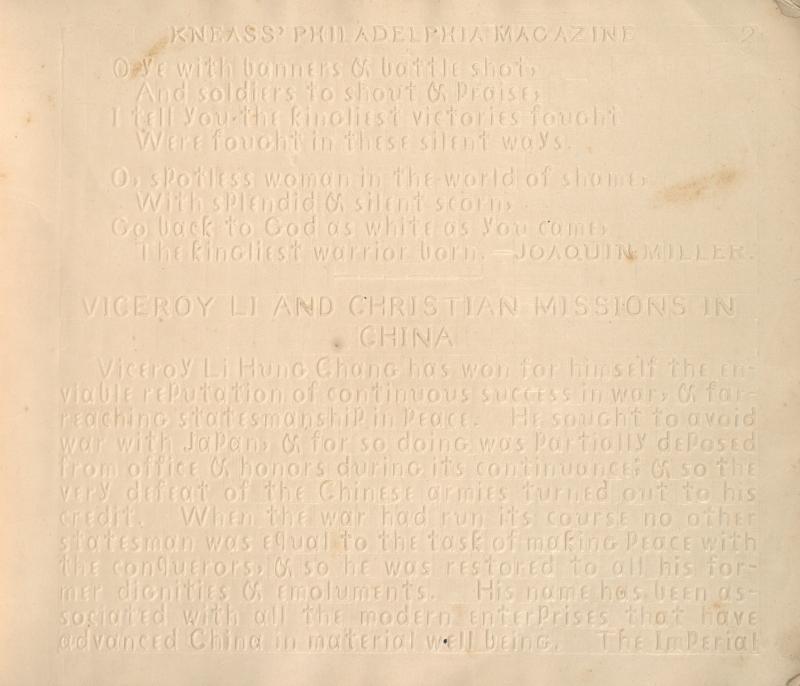

Magazine with raised text that mimics the English alphabet.

The Kneass’ Philadelphia Magazine for the Blind addresses the second focus of this exhibit: the expressed desire to build communities of like-minded and like-bodied individuals. This magazine began in 1867 and produced a long-running raised-print periodical for the blind. A community like this would not have been possible prior to education reforms that broadened accessibility to schooling for the disabled. Schools for the blind increased in the 1830s, allowing a large population of literate people to grow (Jacobs, 2017). This magazine reveals the kind of community blind people created and the values they upheld. One of the values was religious conversion. The article shown tells a doctor’s story where he travels to China, heals people, and converts them to Christianity. Schools for the blind proved that blind people could, in fact, contribute to society in meaningful ways (Jacobs, 2017). They were true citizens that needed to stay up-to-date on the latest developments. Not only did the magazine build a small community of blind people, it also included the blind in the larger Christian community.

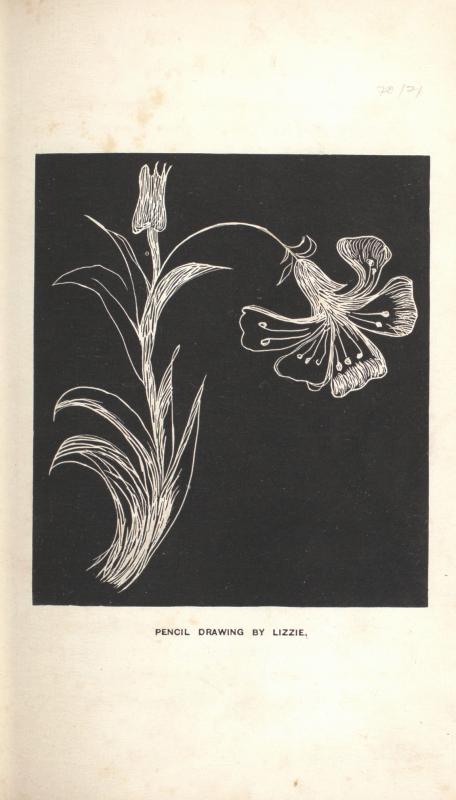

White on black print reproduction of a pencil drawing of a flower.

The reproduction of the “Pencil drawing by Lizzie,” taken from the book The Mind Unveiled, speaks to the trend of boarding children at special schools for “imbeciles.” The Mind Unveiled describes the teaching practices at the Pennsylvania Training School for Idiotic and Feeble-Minded Children, founded in 1852 (Caust-Ellenbogen); the longest running institution of its type, it is still in existence today, now going by the name of Elwyn (About Elwyn). Many of these children were deaf and/or mute, and a few were likely what we now call autistic, or “on the spectrum.” Most of them were miserable, suffering from depression, anxiety, and other conditions resulting from the loneliness felt in reaction to their social isolation. This drawing illustrates the need these children had to communicate with the outside world, often finding expression in the production of art.

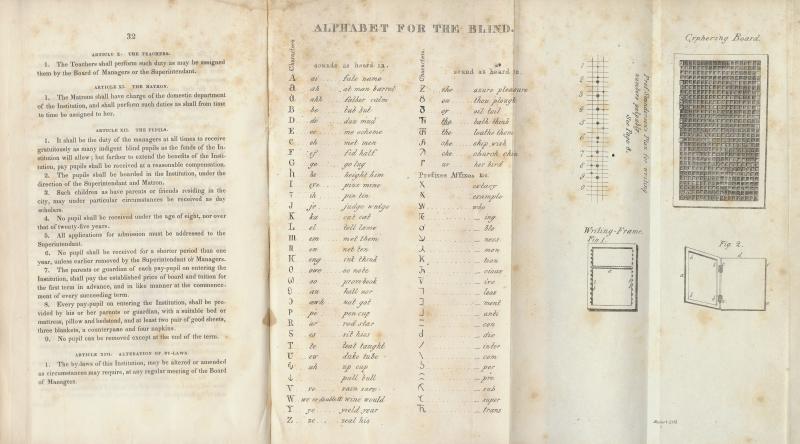

Bylaws of institution, and table and instructions for an alphabet for the blind.

On the left-hand page are some of the foundational bylaws for the institution, not unlike those written to establish a university. In fact, the mission statement for the University of Michigan currently is very similar (Mission). Both express the desire to educate the younger generation in order to build a better future. Both institutions also strived to serve the underprivileged. Article 12 demands that “indigent [poor] blind pupils” be received into the school.

The right-hand page contains an “Alphabet for the Blind,” along with a table and partial instructions for use. This is Boston Line or Raised Text, a form that competed with Braille for popularity in the 19th century (“Touch This Page”). Samuel Gridley Howe promoted Boston Line because of its universal design. Both blind people and sighted people could use the same books if every book was printed in Boston Line. Braille became the more accepted form because it is easier to read and allows the blind to write.

Bibliography

About Elwyn. (nd). Elwyn. Retrieved on March 28, 2022, from https://www.elwyn.org/about-elwyn.

Caust-Ellenbogen, Celia. (2014, December 10). Elwyn and the History of Intellectual Disability. Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Retrieved on March 28, 2022, from https://hsp.org/blogs/archival-adventures-in-small-repositories/elwyn-and-the-history-of-intellectual-disability.

Kerlin, Isaac Newton. (1858). The Mind Unveiled; or A Brief History of Twenty-Two Imbecile Children. U. Hunt & Son.

Melissa Jacobs, (2017) Nineteenth-Century Schools for the Deaf and Blind. Retrieved from the Digital Public Library of America, https://dp.la/primary-source-sets/nineteenth-century-schools-for-the-deaf-and-blind.

Mission. https://president.umich.edu/about/mission/.

“Touch This Page.” https://touchthispage.com/exhibition/welcome-touch-this-page.