Though many disabled people were ostracized by their communities, some found ways to get by and even thrive in the public eye throughout the nineteenth century. In the “Work” chapter of Keywords for Disability Studies (NYU Press, 2015), Sarah F. Rose explains that disability rights activists fought for their place in the labor market as they understood the importance and need for work in order to maintain good social standing (189).

The individuals with disabilities whose traces can be found in the Clements collections were no exceptions to the nineteenth-century race to get ahead. Catherine and Victoria Foster, often called “The Fairy Sisters,” were both below two feet tall. Their parents displayed them around the country, creating an attraction of the “two smallest women in the world.” Justin Wells was an acclaimed writer during the 19th century who used his mouth to write because he was paralyzed. Martha Ann Honeywell, an artist without arms, also used her mouth for her creations, crafting silhouettes and numerous other forms of art before an audience. If some thought him mentally unsound due to his actions and personality, Lord Timothy Dexter’s status and wealth shielded him from negative stigma and rendered him merely “eccentric.” General Tom Thumb (Charles Sherwood Straton) and his wife, Lavinia Warren, who both had dwarfism, achieved incredible fame as performers in freak shows and were even invited to speak with Abraham Lincoln at the White House. Hunter Smith, who had rheumatism (loss of movement in legs), played the dulcimer, which made him famous in Illinois and Iowa. Millie and Christine McKoy, conjoined twins born into slavery, performed songs and dances for packed audiences. Queen Victoria was one of their fans, and met with them on one of their European tours in 1871.

These artifacts do not represent the full scope of working disabled individuals during the nineteenth century. Many disabled individuals were able to find ways of making a living, but few had the wealth or privilege necessary to memorialize their talents and/or have their stories arrive at the Clements. We are limited by the contents of our archive, and can only display so much of the story of making a living while disabled. A person’s disability is often erased from the narrative if they are able to successfully integrate themselves into the mainstream walks of society, even though their disabilities were defining characteristics of their being (Davis 10). The success of the individuals we display is not meant to separate them from more commonly known disability history, but instead, highlights that disability is not always a roadblock to success, but can instead be a launchpad to make a lasting, fulfilling living.

To see the images enlarged, as well as image descriptions, follow the link to each individual image.

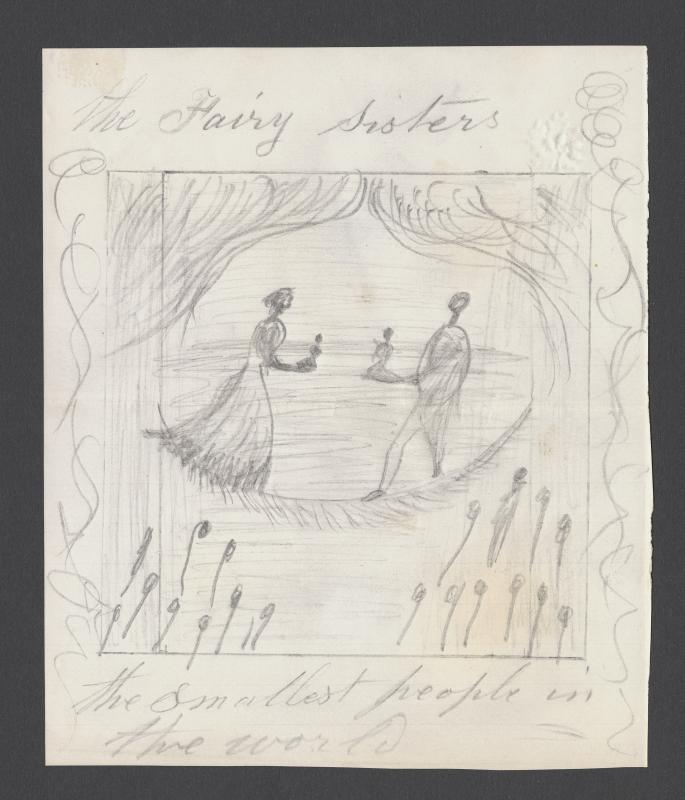

These advertisement sketches by the art company Collins & Chambers, known for their promotional posters for various circus shows, feature Catherine (Cassie) and Victoria Foster, known colloquially as the “Fairy Sisters.” Cassie and Victoria both had a unique form of dwarfism, with some reports citing that they were between one and two and a half pounds each at birth. The sisters began tours around the eastern United States in 1872 and appeared on stage in various outfits alongside musicians and various other performers. Though the girls gained great notoriety for their small stature, with some even claiming they were the smallest people in the world, their careers were short lived. Victoria contracted meningitis at the age of three and a half, and one year later Cassie passed away from an infection at the age of eleven—only three years after they began going on tour. Since the girls were so young during the height of their careers, they had no say in how they were employed, and were forced to be a spectacle by their parents.

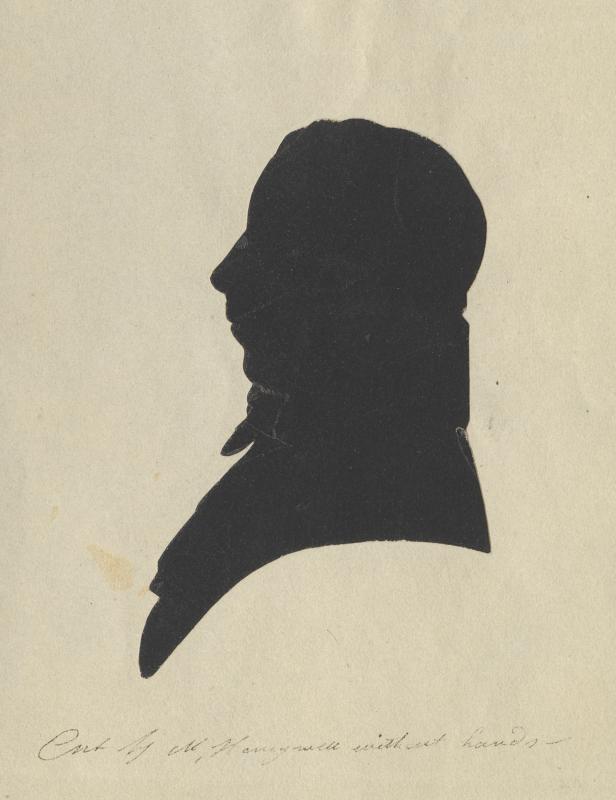

Martha Ann Honeywell, the silhouette artist, was born with no arms, no hands, and only 1 foot with 3 toes. Using her unusual physical form to her advantage, Honeywell became a well-known artist and performer throughout North America, using her mouth to create carved silhouettes, including this one, among other forms of art, for a live audience. Her artistic prowess allowed her to travel across the United States as well as internationally, adding her own unique spin to the common nineteenth-century practice of silhouette creation. Though many disabled artists created silhouettes, Honeywell, through her expert marketing techniques and highly-acclaimed performance tactics, gained great notoriety and fame for her work, and was regarded as an exemplary American woman for her artistic feats (Daen 228). Her disabled form challenged normative American ideals of femininity, making her a truly unique example of how some people with disabilities could make a living by going against commonly accepted expectations.

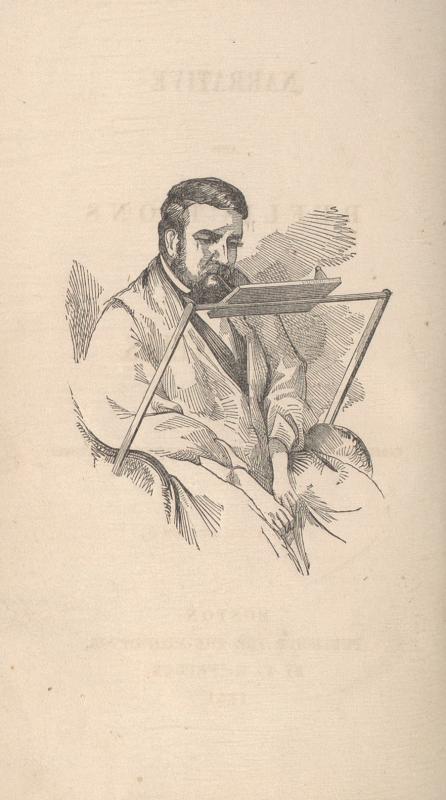

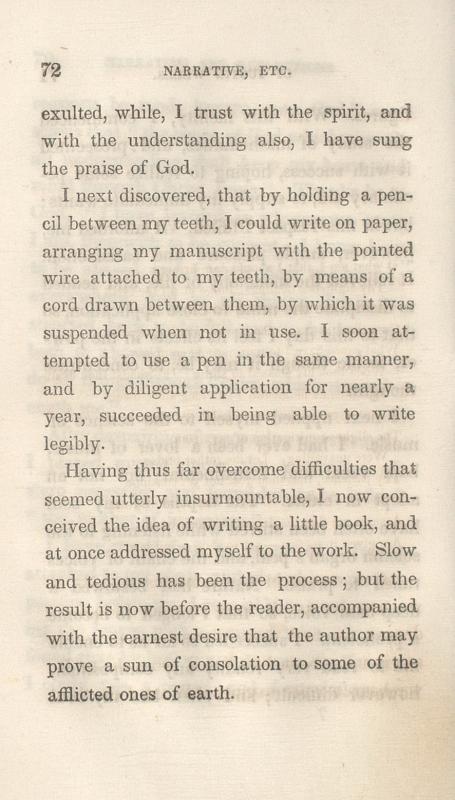

Justin Wells was an acclaimed writer during the 19th century. After contracting an unidentified disease in his adult years, he became completely paralyzed from the neck down, with no ability to move his body other than his head. Wells initially found himself struggling to grapple with his new physical condition. Though considered by many to be an invalid, he spent many years working to operate independently, and eventually prided himself on his ability to work around his newfound disability. With his mind and vocal abilities completely unaffected by his paralysis, Wells wrote by laying a manuscript on his chair, and putting a pen between his teeth, describing this process in detail in the selected passage. He hoped his prowess as a disabled man would inspire other disabled folks, challenging them to find new means of operation, and to find ways to work for themselves.

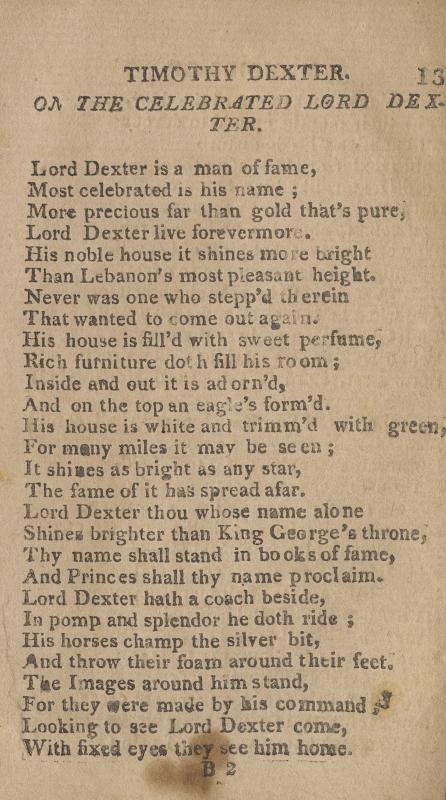

Lord Timothy Dexter was known for foolish business practices. Dropping out of school to work on a farm at a young age, Dexter did not have much of an education. He was often taken advantage of by other businessmen who tricked him into scams such as selling bed warmers and wool mittens to the already warm West Indies, coal to Newcastle, and gloves to the South Sea Islands. Socialites did not accept him, yet he still bought properties in places where they lived. He tried to emulate an eccentric socialite, and decorated his garden with forty statues of famous men. Some believed his reputation as an eccentric obscured underlying mental disabilities, though his wealth shielded him from any major criticisms. He faked his own death, and when his wife did not cry at his wake, he revealed himself and divorced her. He used his memoirs to solidify his legacy, calling himself a “man of fame." His memoir reveals that in the absence of criteria for determining intellectual capacities, those who had the means to finance an extravagant lifestyle could escape the stigma of intellectual disability by casting themselves as eccentrics.

His poem reads:

These three images: one of Tom Thumb and his wife, one of Hunter Smith and his wife, and one of Millie and Christine McKoy, together showcase different ways of being a disabled celebrity. Charles Stratton, or “General Tom Thumb” and his wife, Lavinia Warren Stratton, Hunter Smith, and his wife, Jennie E. Rowe, and Millie and Christine McKoy had disabilities that were deemed “interesting” by society. Consequently, all of them employed their disabilities on the stage in front of an audience.

Hunter Smith, had rheumatism (loss of movement in his legs), which left him disabled. During the years 1850-3, he was educated by Dr. A.C. Price, in which Smith was given instruction of the fundamentals of education, and a desire to read. Smith was eventually provided a chair by Jonas Keck that allowed him to sit upright in 1853, the first time in 13 and ½ years. Hunter Smith then returned from Keokuk County, Iowa to Knox County, Illinois, and started playing the dulcimer in 1854. He then became known as “Little Smith, the dulcimer man.” During this period, Smith became famous across portions of Illinois and Iowa; allowing him to make a living for himself and his wife, Miss Jennie E. Rowe.

Tom Thumb and his wife used their dwarfism to make a living by appearing in a highly popular freak show tour. At age four, Charles S. Stratton, later called “Tom Thumb,” became an immediately popular attraction or “human curiosity” after being discovered by P.T. Barnum in 1842. Throughout Stratton’s early years with Barnum, Charles Stratton was heavily exploited and transformed into General Tom Thumb at the age of eleven before becoming a hit in Europe too. He was one of the best-known “midgets” globally, in both America and Europe. In the year 1863, Stratton married Lavania Warren– another little person employed by Barnum known as “Little Queen of Beauty”– in an elaborately staged ceremony in New York City. They continued to travel with one another, performing across the world.

Millie and Christine McKoy (1851-1912), conjoined twins born into slavery, sang and danced in front of sold-out audiences (including Queen Victoria on more than one occassion). These two young girls were former slaves who became stars on the nineteenth-century circus circuit in the U.S. and Europe. They went by many stage names– “The Carolina Twins,” “The Two-Headed Nightingale,” and “The Eighth Wonder of the World.” Freed from slavery by the Emancipation Proclamation, the girls never again allowed themselves to be displayed in the nude. The twins spent 30 years performing all over the world. After this, Millie and Christine returned and retired to the plantation where they were born. They had inherited it from their father, who purchased the property.