When investigating the interpretation of disability in 19th-century America, it is tempting to take texts at their word. Yet these four narratives written by or about people with disabilities are impossible to separate from the contexts of their creation and the audiences at which they were aimed. A rare, personal account of suffering and confusion brought on by mental illness and addiction, documented in John Hughes’ 1820s letterbook, contrasts sharply with the commercially popular ballad narrating the internal experience of a young deaf girl. The sensationalized biography of “invalid” Leonard Trask provides a counterpoint to the intimacy and tenderness of an Ojibwe folktale about the love between two brothers. Together, the pieces showcase a spectrum of voices narrating experiences of disability throughout the century, and the ways in which their compositional choices were shaped by both genre and audience.

This letterbook is a particularly valuable piece of disability history because Hughes tells his own story, unfiltered through the lens of a doctor’s diagnosis or an outside observer’s assumptions. A picture emerges from the letters Hughes penned to his brother of a man who knew he was prone to imaginations, and who sought to manage these episodes independently to assert and maintain control over his mind and body. In an 1828 letter, Hughes describes a recent episode where he “got in a frolic … which brot. on the imaginations.” For a time, Hughes believed his brother was an enemy, but he reassures his sibling that “I have now completely my health & reason being near four weeks since I tasted a drop of any thing spiritous & from my present Ideas presume I never shall again.” Hughes seems to attribute his imaginations in this passage to excessive drinking – a behavioral pattern that he could conceivably change. It must be noted, however, that he does not consistently blame alcohol for his imaginations throughout the letterbook (Schopieray, 2019). Hughes also shares his own wariness of doctors – a perspective shaped by experience. He tells his brother in another letter that “Should I unfortunately get sick I know as well (probably better) what to do to relieve me than any doctor would. I always keep medicine by me, & the best late authors on medicine.” Hughes goes even further, declaring: “I would not willingly trust my life altogether in any doctors hands, as they are often too fond of trying experiments.” It is telling of the kind of poor treatment Hughes may have received from doctors in the past that he has self-educated about medical matters as a protective step.

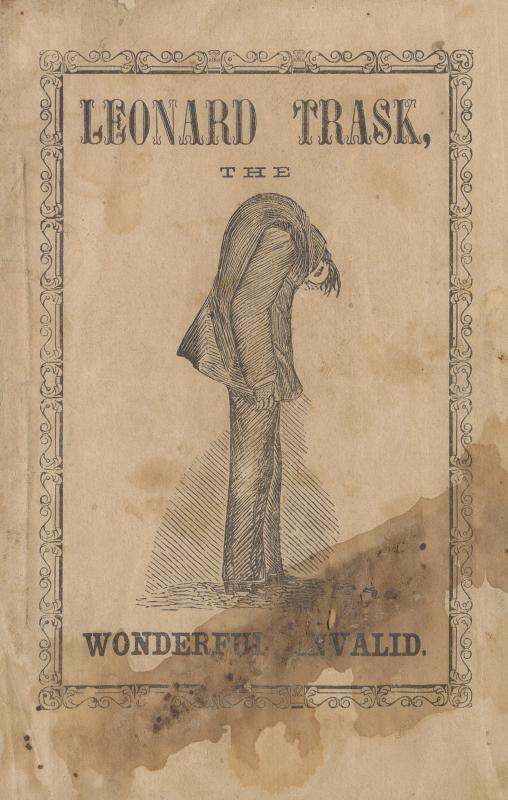

Leonard's back condition made his life difficult. He was a self reliant and very active man, and often used his physical abilities to do heavy work. He built houses, tended to farmland, and was an independent contractor for people in different towns. It is evident he was intrinsically driven. After his injury he attempted to carry on like things hadn’t changed, but they had. He searched for medical practices to “[seek] relief from the chronic disease” (22). All of these medical treatments were experimental and most had unpleasant side effects. No matter what treatment he underwent, the relief would be absent or fleeting. Trask underwent treatment after treatment until he was near penniless. Once he explored every option he returned home to his wife and children. In his later years residing with his wife he came to accept his ailment and learn to live with it. What made this particular injury difficult for Leonard Trask to deal with was that as the man of his household and the provider for his family, without a clear path to make a living, he appears to have thought that he almost had no other use. That is why he travels to the ends of the earth to find a cure, even after many failed attempts. He may have been able to make a living sitting and writing or with his mind, but he didn't adapt in that way. In fact he swallowed his pride and decided to attempt to make a small fortune on his physical appearance. He was told by a friend that a man who looked as uniquely as he did is a man people would pay to see. Yet Trask felt strongly that "he would sell or hire himself to no man, to become a source of speculation in their hands," and that "if his singular form presented to the mind of his fellow men, a subject of curiosity, wonder, interest or instruction, the sight should become a source of profit to no one but himself" (31). Trask tells his life story here in an effort to raise money from sympathetic "patrons." In doing so through a pamphlet that he helped publish, however, Trask appears to have retained a measure of the independence and control of his own narrative that he considered to be so vitally important.

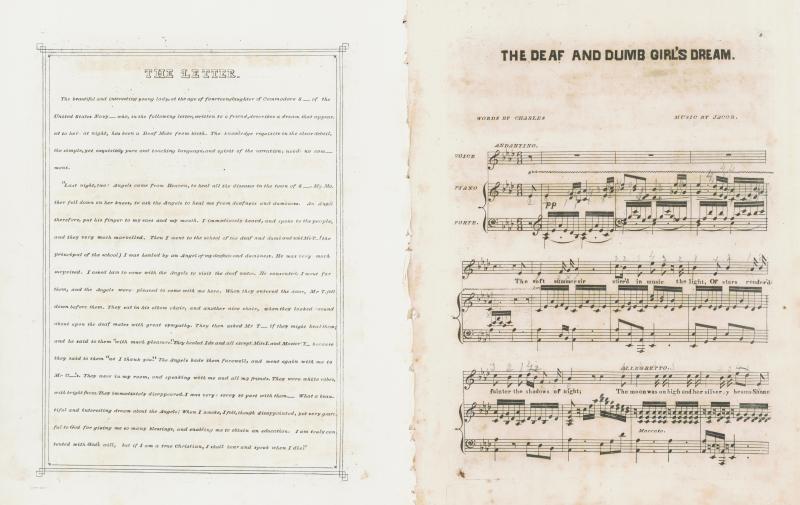

Over the course of the nineteenth century, it became much more common for families (particularly in the middle class) to have pianos at home. Songs like this one may have been performed in public, or privately played in domestic spaces. Pencil notes tell us that someone really used this copy of “The Deaf and Dumb Girl’s Dream.” However, it is unlikely that a musician would have prefaced their performance with a reading of the original source material that inspired it. The letter that prefaces this music slightly contradicts the lyrics themselves in a way that really changes how listeners would interpret the original dreamer's perspective. One distinct difference between the letter that the girl wrote and the song based on the letter is the interpretation of deafness. In the letter she writes “when I awoke, I felt, though disappointed, yet very grateful to God for giving me so many blessings, and enabling me to obtain an education," which she is receiving from a school for deaf children. Meanwhile, the song finishes with lines about how “Her golden dream fled, dreary stillness again, Is her lot!” and “She weeps that the earth, again, gloomy should seem.” The male, hearing composers of this song misrepresent the girl’s dream to their audience, and impose their own opinions on how she should feel about her own life and deafness. The central role that education played in her life, receives no mention in these lyrics - nor does the original letter characterize this deaf girl's life as dreary or upsetting.

A note on terminology: despite being able to communicate using sign language, deaf individuals in the nineteenth century were often inaccurately called "deaf-mute" or "deaf" and "dumb." In the absence of education, deaf children were also often inaccurately assumed to have intellectual disabilities.

The Letter.The beautiful and interesting young lady, at the age of fourteen, daughter of Commodore S__ of the United States Navy – who, in the following letter, written to a friend, describes a dream that appeared to hear at night, has been a Deaf Mute from birth. The knowledge requisite in the clear detail, the simple, yet exquisitely pure and touching language, and the spirit of the narration need no comment.“Last night, two angels came from Heaven, to heal all the disease in the town of S__. My Mother fell down on her knees, to ask the Angels to heal me from deafness and dumbness. An Angel therefore, put his finger to my ears and my mouth. I immediately heard, and spoke to the people, and they very much marvelled. Then I went to the school of the deaf and dumb and told Mr. T__(the principal of the school) I was healed by an Angel of my deafness and dumbness. He was very much surprised. I asked him to come with the Angels to visit the deaf mutes. He consented, I went for them, and the Angels were pleased to come with me here. When they entered the door, Mr. T fell down before them. They sat in his elbow chair, and another nice chair, when they looked round about upon the deaf mutes with great sympathy. They then asked Mr. T__ if they might heal them; and he said to them “with much pleasure.” They healed Ida and all except Miss I. and master they said to them “no I thank you.” The Angels bade them farewell, and went again with me Mr. C__’s. They were in my room, and speaking with me and all my friends. They wore white robes, with bright faces. They immediately disappeared. I was very sorry to part with them.___ What a beautiful and interesting dream about the Angels. When I awoke, I felt though disappointed, yet very grateful to God for giving me so many blessings, and enabling me to obtain an education. I am truly contented with God’s will, but if I am a true Christian, I shall hear and speak when I die.”

This story does not present Bokwewa's “deformity” as a drawback in his life. Bokwewa is depicted as wise, and self-sufficient when he needs to be. His brother’s physical beauty and susceptibility to physical desires are the qualities that put their family in jeopardy. Bokwewa, meanwhile, is able to maintain his focus on the things that really matter in life — like loyalty and supporting your family.

The variety of published items in this collection are products of a thriving market for stories about people with disabilities. Because they are edited narratives intended to make a profit, their content highlights some expectations that many nineteenth-century Americans had for interpretations of disability. Leonard Trask’s pamphlet is complicated, for instance, because many aspects of his commitment to making money for his family are framed as inspirational. However, the most important part of the pamphlet encourages potential readers to stare at Trask’s body: the cover shows an illustration of Trask that centers his dramatically curved spine. In comparison, a deaf girl’s daily reality is used to entertain Americans in their leisure time with this sheet music. The composers interpreted her dream about being able to hear in a way that associates deafness with sadness — a connection that the girl in question did not actually make. By contrast, the Ojibwe folktale originally named “Bokewauway and his Brother,” here retitled “Bokwewa; or, the Humpback” by anthropologist and Michigan founder Henry R. Schoolcraft, takes the focus away from the titular character’s “deformity.” The story itself is about Bokwewa’s relationships, not his body. It is clear that Schoolcraft — whose half-Ojibwe, half-Irish brother-in-law collected and translated the stories in this book — was making editorial choices that reflected the perceived interests of a western audience.

Works Cited

Schopieray, Cheney J. “‘Temperance, Exercise, & Cheerfulness’: The Letter Book of John Hughes.” Clements Library Associates: The Quarto, no. 51 (Summer-Fall 2019): 16-17, https://clements.umich.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/quarto51-our-favorites.pdf.