In this section, the items displayed serve as a microcosm of the economic niche within the greater US economy that people with disabilities created for themselves. If the nineteenth-century American economy could be characterized with one word, it would be “laissez-faire”—the economic idea that the government would only minimally regulate its economy. This allowed corporations to prosper in the mid to last few decades of the century as an industrial revolution allowed for cheap, quick manufacturing of many goods that once required specialized labor to create.

American industrialization was a double-edged sword to many people at the time. While mass production allowed for consumer goods to be affordable and available to more people than ever, it also changed the American economic structure to be increasingly manufacturing-based, which required an able body to work long, unregulated hours. As a result, mobility devices like wheelchairs and readers would become available to physically impaired Americans, but many of these potential users would not be able to generate the income needed to purchase them.

The items in this case demonstrate both sides of this dichotomy that industrialization brought to disability culture within the United States. Pamphlets like What We Make demonstrate the new, novel mobility devices that were available to those that could afford them during this time period. On the other hand, in an era of free-for-all economics with little regard for social welfare, disabled Americans who couldn’t work physical jobs had to invent their own unique way to communicate with each other, make a living, and advocate for their communities.

To see the images enlarged, as well as image descriptions, follow the link to each individual image.

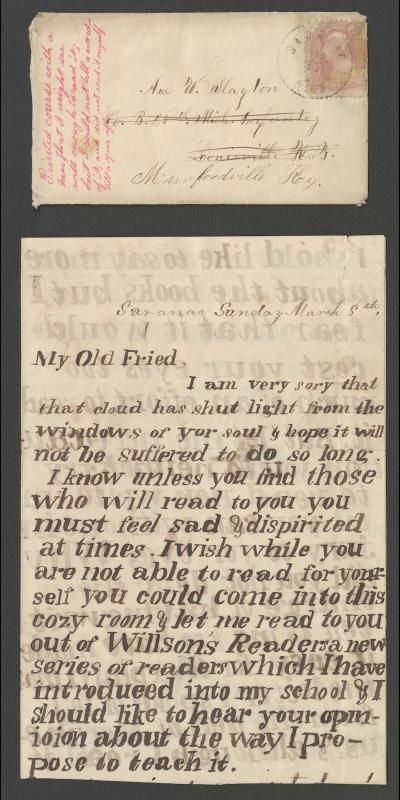

This letter was written by a woman named Mary J. Rogers to her friend, the Civil War hero Asa W. Slayton, who experienced loss of sight. The letter originates from Saranac, Michigan and details that the woman hoped the unusual font, made up of letters of different size and thickness, would aid Slayton’s ability to read as his eyesight weakened. In the letter she expresses warm regards and proceeds to ask for advice from her dear friend Slayton, whom she valued as a teacher.

On the envelope, Slayton admits that the font did not help as his eyesight was fully deteriorated by the time he received it, but that he was able to read it a year later.

The History of the Slayton Family, compiled in part by Asa W. Slayton, explains that his vision deterioration was due to “inflammation in the eyes” and lasted around three years. A sergeant in the United States Military, Slayton eventually returned to Michigan to teach.

In an era prior to common practices to help those with a loss of eyesight read, solutions had to be invented on the fly and, as this letter exchange reveals, not all of them worked.

The letter reads:

“Saranac Sunday, March 8th,

My Old Friend,

I am very sorry that that cloud has shut light from the windows of your soul & hope it will not be suffered to do so long.

I know unless you find those who will read to you you must feel sad & dispirited at times. I wish while you are not able to read for yourself you could come into this cozy room & let me read to you out of Willsons Readers a new series of readers which I have introduced into my school & I should like to hear your opinion about the way I propose to teach it.”

On the envelope, written by Asa, are the words “Printed coarse with a pen, that I might see well enough to read it, but I could not tell a word of it, and did not read it myself till a year after.”

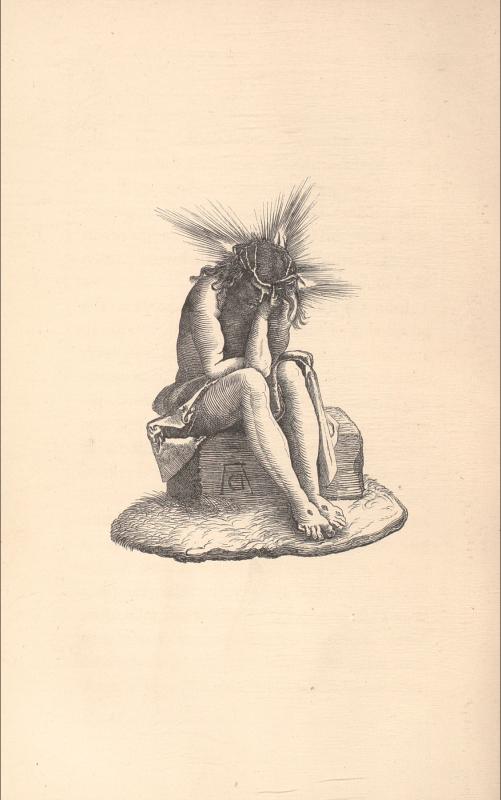

The Life of John Carter is the biography of an artist from Essex, England who created ink drawings with his mouth due to an injury that left him paralyzed from the neck down. In this book, you can find stories of Carter's life in addition to various samples of his art, which represents a range of subjects from animals to landscapes to religious figures.

The selected page of this book for the exhibit highlights one of these samples of his work, a representation of Jesus Christ. In this representation, Christ is shown sitting on a box with his head in his hands. He wears only a cloth on his lap and the crown of thorns. There are holes in his shoeless feet. Behind his head are many lines depicting light in the form of the top of a cross. These lines are a common motif in Carter’s work, especially in his religious pieces, and are a sign that Carter could be mimicking line engravings to make his works more mass-producible to be sold to earn a living (Henderson). It also clearly demonstrates the precision with which Carter could draw with his mouth. While Carter was making his own art accessible for himself, he also found it necessary to use whatever skills he had to make a path for himself in an industrialized economy.

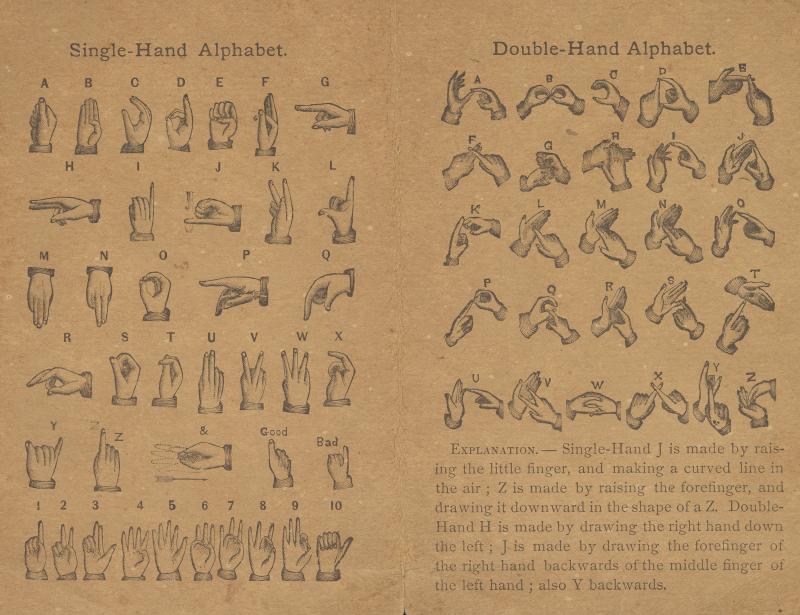

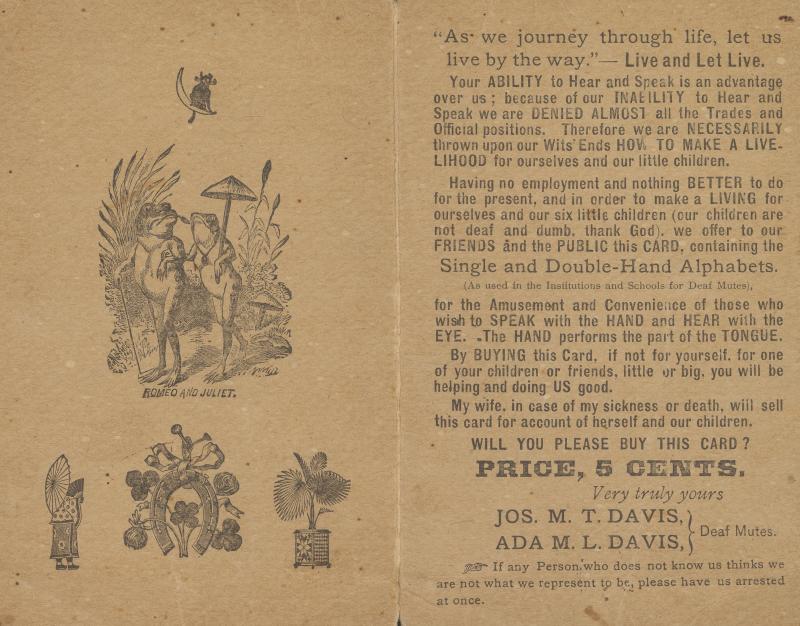

The cover page of this undated, yellowed pamphlet states that the authors, husband and wife deaf-mute duo Jo. M. T. Davis and Ada M. L Davis are publishing this pamphlet to provide for their six hearing and speaking children. They write that the least the non-disabled public can do is to buy this pamphlet, as their ability to hear and talk is an advantage over the deaf-mutes.

Unable to make a traditional living for themselves in a hearing, talking world, the Davises relied on the general public as a source of income. However, not much is known about the Davis family, so there is no way to tell if their motive in selling this pamphlet was simply to support themselves financially or if it was also created to spread awareness of deaf-mute issues and to widen the circle of people who use American Sign Language.

Their emphatic plea reads as follows:

“As we journey through life, let us live by the way." – Live and Let Live.

Your ability to hear and speak is an advantage over us; because of our inability to hear and speak, we are denied almost all the trades and official positions. Therefore we are necessarily thrown upon our wit’s end how to make a livelihood for ourselves and our little children.

Having no employment and nothing better to do for the present, and in order to make a living for ourselves and our six little children (our children are not deaf and dumb. Thank God), we offer to our friends and the public this card, containing the Single and Double-Hand Alphabets. (As used in the Institutions and Schools for Deaf Mutes), for the amusement and convenience of those who wish to speak with the hand and hear with the eye. The hand performs the part of the tongue.

By buying this card, if not for yourself, for one of your children or friends, little or big, you will be helping and doing us good.

My wife, in case of my sickness or death, will sell this card for account of herself and our children.

Will you please buy this card?

Price, 5 cents.

Very truly yours,

Jos. M. T. Davis and Ada M. L. Davis, Deaf Mutes.

If any Person who does not know us thinks we are not what we represent to be, please have us arrested at once.

The signs shown on the pamphlet are the same signs used by deaf and mute communities today. In 1817 at the Hartford Asylum for the Education and Instruction of the Deaf and Dumb, the Martha Vineyard’s Sign Language and French Sign Language were merged to become what we know as American Sign Language (Weitbrecht, 2022). As the pamphlet specifies that it teaches the sign language alphabet taught in American institutions, we can date the pamphlet to sometime after 1817.

See the Works Cited page for the full citation.

Published in 1904, The life of Sergeant George R. Shebbeard is a small, worn booklet with a light brown cover that could easily fit in your hand. This is a first-hand account of George R. Shebbeard, a New Jersey Civil War veteran who suffered an internal injury after falling off of a horse, preventing him from being able to walk. Within are 32 pages detailing Shebbeard’s journey from being ten years old to joining the army, his injury, and then living as a disabled person.

Accompanying this booklet—not shown here—is a photograph of Shebbeard himself. At 64 years old, he is a portly man who lays on top of a wheeled cart that is assumed to be his mobility device. The back of the photograph, not pictured here, has a small sticker in the upper right-hand corner that reads: I was injured at the Battle of Fair Oaks, June 1st 1862. I have been helpless for 17 years. I have lived in this little wagon 20 inches wide, 52 inches long for 10 years, and never get tired; I am 64 years old. I have traveled since 1892. Attended 8 G.A.R Encampments. Aug. 25 1904.

Although Shebbeard was confined to his wagon, he did not let that stop him from his various endeavors in life. By his own account, he got around fairly well and, as listed above, even attendended several gatherings of the Grand Army of the Republic, a Civil War veterans organization.

Shebbeard’s pamphlet is only one of the ways that he supported himself- in the Journal of the House of Representatives of the United States, Volume 62, Issue 1, Shebbeard is specifically mentioned in a bill regarding a pension raise, indicating that he had successfully lobbied his local state representative to improve his life and the lives of other disabled veterans. While his impact on greater American politics may have been minor, Shebbeard’s political action is another example of how physically impaired war veterans used their own ingenuity to make a living.

See the Works Cited page for the full citation.

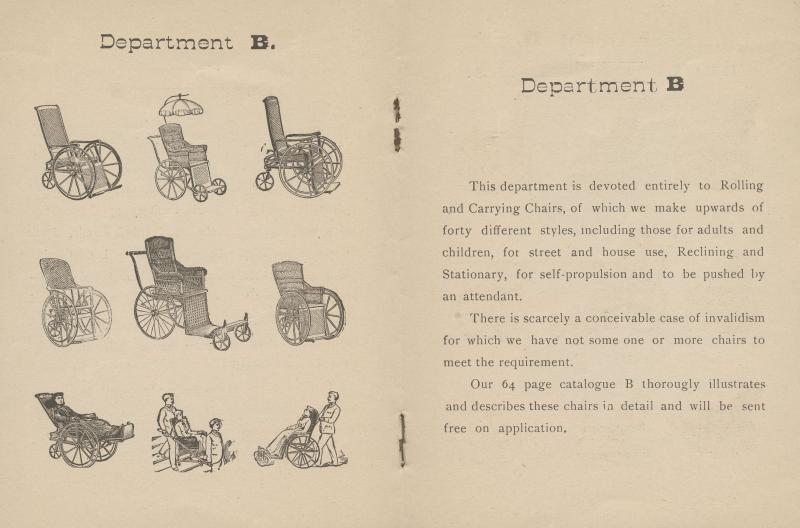

This is an advertising pamphlet called What We Make, created by the Sargent Manufacturing Co. in Muskegon, Michigan. It contains pictures and descriptions of mobility devices designed for those with various physical impairments. Sargent Manufacturing Co. sent out this pamphlet for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago with the intention of reaching a global audience.

The fact that a large manufacturer like Sargent was selling relatively affordable mobility devices demonstrates the ubiquity of physical impairment in Reconstruction America. Although many mobility devices such as wheelchairs had existed on a small, individualized scale since the 17th century, only in the late 19th century did manufacturing technology and consumer demand catch up. Demand for these devices was high enough to warrant mass production by a manufacturing firm with branches in New York City, Muskegon, and Milwaukee, with exports all over the continental US and overseas to London (The Advantages and Surroundings of Muskegon, Mich., 1892).

Works Cited

Henderson, Thomas Finlayson. Carter, John (1815-1850). Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

Sargent Manufacturing Co. 1893. What We Make. Muskegon, Michigan.

Slayton, Asa W. History of the Slayton Family: Biographical and Genealogical. 1898.

https://tinyurl.com/pz4p6jk6.

“The Advantages and surroundings of Muskegon, Mich.: the material interests of a progressive city.” n.d. quod.lib.umich.edu. Accessed March 28, 2022. https://quod.lib.umich.edu/m/micounty/5423913.0001.001?view=toc.

Weitbrecht, Robert. n.d. “Deaf History Timeline | American Sign Language at Harvard.” Projects at Harvard. Accessed March 28, 2022. https://projects.iq.harvard.edu/asl/deaf-history-timeline.

Journal of the House of Representatives of the United States: Volume 62, Issue 1. 1911. N.p.: U.S. Government Printing Office. https://books.google.com/books?id=p2RQAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA593&lpg=PA593&dq=george+r+shebbeard&source=bl&ots=jfJbD4KuDA&sig=ACfU3U2JbWUy4VuAoT_5oPeztRTPyW9sAw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjkkJKunun2AhWTQc0KHTKSDuoQ6AF6BAhCEAM#v=onepage&q=george%20r%20shebbeard&f=false.